The original Columbia recording of Duke Ellington’s piano feature The Clothed Woman is from December 30th, 1947, and is available on “The Chronological Duke Ellington and his Orchestra 1947-1948.” Ellington had performed the piece a few nights earlier at Carnegie Hall. I first heard the studio version on a cassette compilation years ago.

I’ve since heard Dick Hyman and Marion McPartland’s live recordings of The Clothed Woman, and I’m sure many others have attempted to recreate this magical work.

This work has been described as enigmatic, angular, ahead of its time, revolutionary, and dissonant. There’s a tremendous amount of content within the simple ABA form: a dissonant “A” intro and outro surround a “B” stride/swing improvisation.

Invariably, everyone I’ve read, including the esteemed Gunther Schuller, label the “A” section “atonal”, and this is how I first heard it. It’s really hard to get a grasp on what Duke is doing here–it sounds like a barrage of modernist cluster chords, and it seems like there’s no functioning harmony. I had a revelation on perhaps the fiftieth time I listened, though. I had it sketched out, and I was trying to figure out where to put the barlines…then I heard it…(sorry Maestro Schuller)…

The A section is not atonal. Far from it. The “A” section of this amazing work is a twelve bar blues in F.

Dissonance is not necessarily atonal. In fact, the seemingly modernist structures and harmonies Duke lays out for us here in this piece are all well within the bounds of the modern jazz harmonic language. Nevertheless, its structure and tonality is elusive, and the piece certainly exceeds most listeners’ ability to follow form and chord changes. It sure exceeded my own. Yet, as “out” as it sounded to me in the 90’s when I first heard it, I can only imagine how it struck the ears of a 1940’s jazz audience.

Here’s my transcription:

The Clothed Woman–transcribed: Healy

And the studio recording:

The first “blues clue” is the overall tonality of the A section. Listen hard–we’re clearly in the key of F. The second clue is the strong move to the IV chord–straight ahead blues language (m.5 on my transcription). Once I “got” this I was hooked. I transcribe the A section, and played it a few times before it made sense. Then, all at once, every note, even the most “dissonant and atonal,” fell into place. Duke is playing around with an F blues, using wide left hand voicings, punctuated by right hand grace note runs, chords and cluster-y structures that embellish the basic I-IV-V tonality and blues form.

Following the A section there’s quick band interlude with rhythm section and couple of horn figures, then comes the B section, which is definitely not blues. I’ve heard a live recording of Ellington perform this swinging 4/4 semi-stride solo piano section by itself as a tribute to Willie “The Lion” Smith. Then comes the last A section–a repeat of the first with a few minor changes, and a strong bluesy tag and walk-up cadence.

A-B-A form, where A is a blues and B is a contrasting interlude piece, was not a new Ellington device. Duke had done this long form before, sandwiching a real tune in between bookends of the blues. He recorded Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue in 1937 with a short piano interlude bridging the two sides of the 78. Yet when he performed it publicly in 1945, he experimented by replacing the middle interlude with Rocks In My Bed, Carnegie Blues and I Got It Bad, and renamed the entire suite Blues Cluster. I think we have a similar situation with The Clothed Woman: ABA form: blues/tune/blues.

He hadn’t done anything as “modern” as the A section of The Clothed Woman before, as a soloist or as a writer–such angular momentum, extended harmony, crunchy grace note figures, a rubato, slow groove with an implied swing, all with wide leaps across every register of the piano. Who else was doing this? Thelonious Monk? Monk was just getting going as a recording artist in 1947, in fact he recorded his first record that year. He was however big on the scene, and the house piano player at Minton’s at a time when NYC was abuzz about the emergence of bebop. Like Ellington, Monk was pushing the envelope for many years. Threads of modern jazz piano and new harmony reach back to the late 1930’s, and even the 20’s with James P. Johnson–Ellington was on the scene in NYC in the 40’s, Strayhorn lived in Harlem–they must have gotten more than a whiff of Monk’s new thing. They certainly seem to share a similar harmonic outlook: playing extensions on the dominant chord, triads over bass pedals, lots of substitute dominants and chromatic embellishments. Perhaps Strayhorn is the wild card; did his command of harmony and dissonance, and his piano chops seed The Clothed Woman? Something did—this work is an unprecedented masterpiece. Real historians, please chime in.

Here’s some music theory, get the coffee:

The Clothed Woman begins with a high chord hit, then a swooping downward arpeggio ending on a Gb, which resolves down a step to F (Ex.1.). The structure is diminished scale tones in repeating intervals–with the Gb in the bass and it sounds like Gb7(#9)–an altered chromatic “tritone” substitute for the V chord in the key of F–a perfect intro (Ex.1.) It’s a spooky chord no matter what you name it, and the harp-like arpeggio adds to the exotic quality of the intro. Play it with the pedal down, if you can with just your right hand. If you can’t, grab four notes with the RH, the next 4 with the LH, cross over the RH, etc…but that’s hard to pull off and make it smooth.

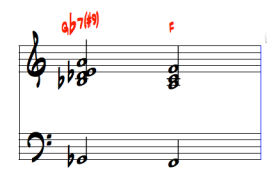

Ex 1. Duke’s descending run on “The Clothed Woman” which outlines Gb7(#9)–here with enharmonic spellings to show the structure of the voicing: minor 3rd and perfect 4th separated by a half step.

A basic harmonic device in the piece is the substitute dominant, or tritone sub. Chromatic voice movement and strong, melodic resolution are what this makes this progression work (Ex. 2.)

Ex. 2 The movement of Gb7(#9) to F major is good example of the chromatic chord and melody movement in this piece. Gb is a substitute dominant, or V7 chord–put a C in the bass and it’s C13(b9). This is certainly not atonal.

Many of the RH grace note licks have motivic similarities, and they fit the hand well. In Ex. 3 three of the grace note figures share common notes: an Ab triad. The Ab-A “blue note” motion reinforces the blues feeling, and provides chromatic embellishment.

Ex. 3 The texture the Ellington establishes, grace note to chord, is angular, austere and evocative. In this example he sets up movement to the IV chord with I-V-I- bII7/IV then the IV chord. He also uses the C alt scale, a more exotic sound. Or is it a diminished scale? Who cares!

One way to approach the style of The Clothed Woman is to think of the grace notes having a dual function: melodic upper extensions and stratified harmony. The hands are separated, and so are the strata of the harmonies (Ex. 4.)

Ex. 4 In M 5-6 RH grace notes move to chord structures on the strong beats. On the third beat of M5 the chord is Bb7(b9b5)–but also it’s also an E triad over a Bb triad. On the fourth beat the triplet is both an E13(#5b9), or Bbmi9 (or Dbmaj7) over an E triad–polytonal, melodic, dissonant, separated and stratified.

What seems atonal and dissonant is actually functional harmony, like this passage from M 8-10 (Ex 5).

Ex. 5 Passing chord Abdim moves down to G7(b5) then to C9, which begins the II-V of the blues progression. Then back to what might be called a Gmi7 in inversion, then to E7, which moves up to F to complete the cadence. Grace notes embellish from above, but also from the side chromatically. This passage requires the RH over the LH.

Here’s me playing The Clothed Woman with my trio last May at Vitello’s in Studio City, CA with Carlos Del Puerto on bass and Bill Wysaske on drums:

This is an incredible piece of music, and I appreciate the time you have taken to break down why this piece is so progressive for the era in which it was written. It is also a piece of Ellingtonia that is missing in my collection. I am looking forward to spending time with this. Thank you.

Thanks Michael, I hope you can spend some time with it. I’m seeing now that it is one of the most important piano statements of the era. It shows Duke’s connection with both the audience and with the intricacies of the emerging early bop/post swing sound. Plus the fact that he could perform it one night and record it almost note for note in the studio later means that it was far from just a tossed off improvisation. The fact that it is mostly ignored or misunderstood is just another indication of the same sentiment that I believe keeps Ellington out of the schools. As vast as his output was and as varied as his writing could be, he is branded “old-school”, having never made the transition to be-bop or the “new thing.” Everyone loves “Ko-Ko” and “Harlem Air Shaft” and Strayhorn’s “Take the A Train” and “Satin Doll,” but is Ellington’s other work considered artistically “up there” with that of Gil Evans, Miles Davis and Gerry Mulligan? Everyone talks about the “Thad Jones sound…” whos roots are in Dukes and others’ works in the 1930.

This post is getting a lot of hits, in fact it’s top of the Google search for “The Clothed Woman”, thank you SEO…I am fixing typos and transcription inaccuracies, so let me know if you see any. Thanks!

I’m continuing to update and refine this post, since it seems to be #1 in google search for “The Clothed Woman”, I want to make sure I’ve got it right. I’m still waiting for the call from Mr. Schuller (of whom I am a tremendous fan BTW).

Dear Scott

Three of us in the Duke Ellington Society UK gave Clothed (30-12-47) a spin at my home yesterday, following the Columbia with Duke’s solo version in his Museum of Modern Arts recital (4-1-62). It stemmed from Marian McPartland’s solo version recorded at Maybeck Hall (Concord) in, I think, 1991. Bill Saxonis (Albany, NY) featured that in his annual Ellington birthday radio show this year…

I digress. The purpose of this reply is to ask if I can use your thought-provoking material as an article in Blue Light, the DESUK quarterly magazine of which I am managing editor.

Yours

Geoff Smith

Absolutely, I’d be honored.

Pingback: Introduction (Podcast #16-001) | Ellington Reflections